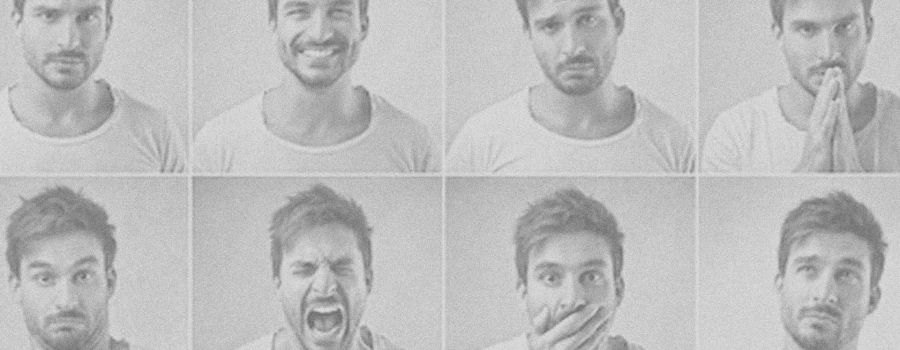

Tough emotions – stress, anxiety, fear – hold a lot of power over the way we perform, learn, and handle setbacks.

We feel nervous before a big game or presentation and don’t perform our best.

We’re presented with a challenge, we feel uncomfortable, we decide we’re not ready.

We feel weird about speaking up or asking a question and then we choose to not ask or answer.

We’re facing a setback, we feel sad, angry, embarrassed, we do everything we can to stop feeling like that.

All of these scenarios have one thing in common: our tough emotions are driving our behavior, and usually in the wrong direction. This isn’t a comprehensive list. You and I could come up with a few hundred more examples if we had the time.

So what to do?

On the surface, this seems simple: give tough emotions less power by getting rid of them, by not feeling them. Think about the examples above. What would you tell yourself or someone else in those situations?

Allison Wood Brooks, a researcher from Harvard Business School, designed a study asking a similar question:

“Imagine that you work in a large organization of about five hundred employees. Tomorrow, you are scheduled to give a thirty-minute keynote speech in front of the whole company, including the CEO and executive board. This makes you feel extremely anxious.What advice would you give yourself or someone else?”

Nearly 90% of the participants believed that the best approach is to “relax or calm down” – to not feel.

This advice is coming from a good place and seems logical: if our tough emotions cause problems, we should try not to feel them, so we say:

“Just be positive.”

“Toughen up.”

“Calm down.”

“Don’t worry.”

“Don’t be afraid.”

“Be fearless.”

There are two main takeaways from this messaging:

1. Feeling bad is bad

2. It’s best to avoid and not feel the tough emotions

But if we dig into it a little, this “don’t feel” approach causes more harm than good.

Don’t Feel Approach Problem #1: We can’t really do it

Regions of our brain are designed to generate discomfort to keep us out of danger, which is a fantastic survival tactic.

We hear a rustling in the bushes, we feel afraid, we bolt.

We’re walking near the edge of a cliff, we feel anxious, we stay away from the edge.

These brain regions are not advanced enough to gauge the particular situation we’re in – instead they scan the environment for triggers like uncertainty, attention, change, and struggle, among others. If we’re doing something that involves one of those triggers, we’re going to feel uncomfortable whether we’re in danger or not.

This tactic is extremely effective when we’re in danger. Not so much when it comes to learning and performance.

Things that take us out of our comfort zone but are usually not dangerous:

Giving a presentation

A change in the workplace

Learning a new skill

Playing a tough opponent

Obviously none of these things involve real danger, but part of our brain thinks they do because some, if not all, of those triggers are at play – we’re being watched, judged, the outcome is uncertain, and struggle is involved.

It’s human nature to feel discomfort when we’re out of our comfort zones. If we care about something and it involves uncertainty, attention, change, or struggle, we will feel tough emotions. We can’t stop a part of our brain from doing its job.

Feeling tough emotions before a big test, presentation, or game doesn’t mean we’re doing something wrong, that we’re not prepared, that we don’t belong – it means we’re human. Humans are built to feel, yet we’re told not to. Which is the equivalent of telling someone not to sweat when it’s hot out.

Don’t Feel Approach Problem #2: It makes them worse

If you look into the research of stress, anxiety, or fear, piles of studies show that one of the worst possible approaches to dealing with tough emotions is to try to suppress them.

James Gross from Stanford put people in high stress situations and measured brain activity. Telling people to suppress their feelings actually heightened the activity in the fear centers of their brains – making the feelings even more intense.

When we say “calm down” or “don’t be afraid” we’re essentially saying “don’t feel how you feel,” and the next logical approach is to try and suppress the emotions.

Encouraging suppression also creates a lot of shame around tough emotions.

If I’m told to not feel, but then I’m in a situation where I do feel, I assume that something is wrong:

“I’m not supposed to feel like this, but I do. Something’s wrong, I’m not ready, nobody else feels like this. I don’t belong.”

Shame around our feelings creates a snowball effect. Rather than getting rid of the emotions, we applify them. We feel ashamed for being afraid, worried that we’re nervous, weak because we are sad. This is one of the root causes of imposter syndrome and a lot of our limiting beliefs.

Years ago when I first started doing workshops, I fell into this trap all the time. Before every presentation I was super nervous – I was too young, not smart enough, not ready for something like this. I interpreted those feelings of uncertainty as a sign of weakness.

And in the midst of a tough breakup I can remember shaming myself for being weak because I was sad, hurt, and embarrassed.

Our flawed assumptions around tough emotions usually make them worse.

Don’t Feel Approach Problem #3: Avoiding the emotions robs us of growth

Let’s take this from the top.

1. You and I are both humans, which means

2. You and I will both face setbacks and situations that stretch us out of our comfort zone, which means

3. You and I will both feel tough emotions

4. The way we’re trained to think about tough emotions makes them worse, which means

5. We’ll attempt to get rid of them

When we’re feeling tough emotions, we come up with a bunch of strategies to stop feeling:

Suppress/Deny – push them down and bottle them up (for as long as we can)

Numb – food, drinks, activities to minimize the pain

Offload – blame someone else, lash out at others to share the pain

Hide – stop doing the thing that caused the pain

Think of these as pain relievers we use to stop feeling. They usually work, but it comes at a cost: pain relievers rob us of opportunities to grow.

Let’s go back to my breakup. I’m feeling all my tough emotions, I interpret it as weakness, and I opt for some offloading. I blame it all on her – she’s the worst!

As soon as I got there, I felt much better. It’s all her fault, so I don’t need to be sad, angry, or embarrassed.

Sure that helped me feel better, but did I grow? Of course not. Putting all the blame on her helped dull the pain, but it blinded me to the role I played in the breakup and the lessons that could have made me better for my next relationship.

The same rules apply to struggling on a test – if I put all the blame on my teacher, I feel better, but probably won’t grow.

If I apply for a job, go through the interview process, and get rejected, I’m going to feel a lot of tough emotions. It would be easy to relieve pain by hiding: if I stop applying for jobs, I won’t have to feel like this again.

Pain = gone

Growth = gone

This “don’t feel” approach doesn’t work because we can’t really do it, it can make the feelings worse, and it drives negative actions that can hurt our capacity to grow and the people around us – so yeah, it’s not great.

Of course feeling tough emotions isn’t always fun, but it’s the price of admission we have to pay if we want to grow. This doesn’t mean we just sit in the swamp and do nothing. It means we have the courage to feel, get curious, and do the next right thing.

The key here is to see that it’s not the tough emotions that cause problems. It’s the way we’re taught to think about, talk about, and interpret these emotions that creates these problems.

Our assumption that it’s bad to feel bad is the root cause of it all.

And that, my friend, is where the solution lies. We have to recalibrate our original assumption about tough emotions. If we can learn to understand and accept our tough emotions, we can learn better, perform better, and become more resilient.

The Solution: Follow the Science & Accept

Jeremy Jamieson gives a group of Harvard students a series of questions from the practice GRE exam. They’re given no special training or instructions. They complete the exam and score an average of 684/800.

A second group of students is given the same set of questions but receives one paragraph of instructions teaching them to reappraise their emotions: “feeling nervous before an exam is human, it’s normal, it can be a good thing.” They score a 739/800.

Three months later all of the students took the real GRE and a similar gap remained. This was one session, one day, one paragraph. There was no further contact with the students. Yet, three months later the students that learned that it’s ok to feel did better than the students that didn’t.

Making a small adjustment to the way we think about tough emotions can make a big difference.

Alia Crum set up a study that showed the benefits this can have in the workplace.

Participants watched a series of videos that either framed stress as a positive or negative. The group that learned to accept and understand stress actually saw improved health and work performance.

Perhaps the most interesting discovery from research like this is that all of the participants feel the same. In stressful situations their heart rates increase, blood pressure rises, and hormones change a bit – no matter how they frame the emotions.

And that is one of the big points we’re trying to drive home here. We don’t have much control over our emotions, how we feel. But we can control the way we interpret our emotions – which can either help or hurt us.

When we’re working under the assumption that the stress is a negative thing, then we’re put into a situation designed to make us feel anxious, how do we interpret those feelings? As a negative. And then our attention is directed to the discomfort: “Why am I feeling this?” “Feeling this is bad.” “How do I get rid of this?” No wonder our performance suffers.

On the other hand, if we’re taught that it’s ok to feel, we can acknowledge the discomfort, avoid shaming ourselves for feeling, and turn our attention to the task.

Huddle 1:

We’re standing close together. We’re playing our biggest rivals. Stands are packed. It’s a huge game. Our coach, recognizing our heightened emotions, steps into the huddle and tells us all to calm down.

Huddle 2:

We’re standing close together. We’re playing our biggest rivals. Stands are packed. It’s a huge game. Our coach, recognizing our heightened emotions, steps into the huddle and says: “I’m feeling it right now, and I know you are too. That’s a good thing, it means that this is a big moment, and it means you care – let’s go battle.”

Replace the game with a presentation, job interview, or test, and this is a framework we can all use.

Not only will this approach improve performance, but it can have a huge impact on how we grow. I can think of so many times in my life where I was presented a big opportunity but I avoided it because it made me feel uncomfortable. My emotions carried so much power and drove a lot of my decisions.

We take the power away from our emotions not by fighting them or suppressing them, but by learning to understand and accept them. This is easier said than done – but it’s also one of the most courageous things we can do for ourselves and the people around us.

There are more strategies we can deploy, some are outlined on this podcast. But the big idea here is that if we want to become a better learner we need to change the way we think about tough emotions. It’s not bad to feel bad. We’re all humans and it’s usually best to work with our nature rather than against it.