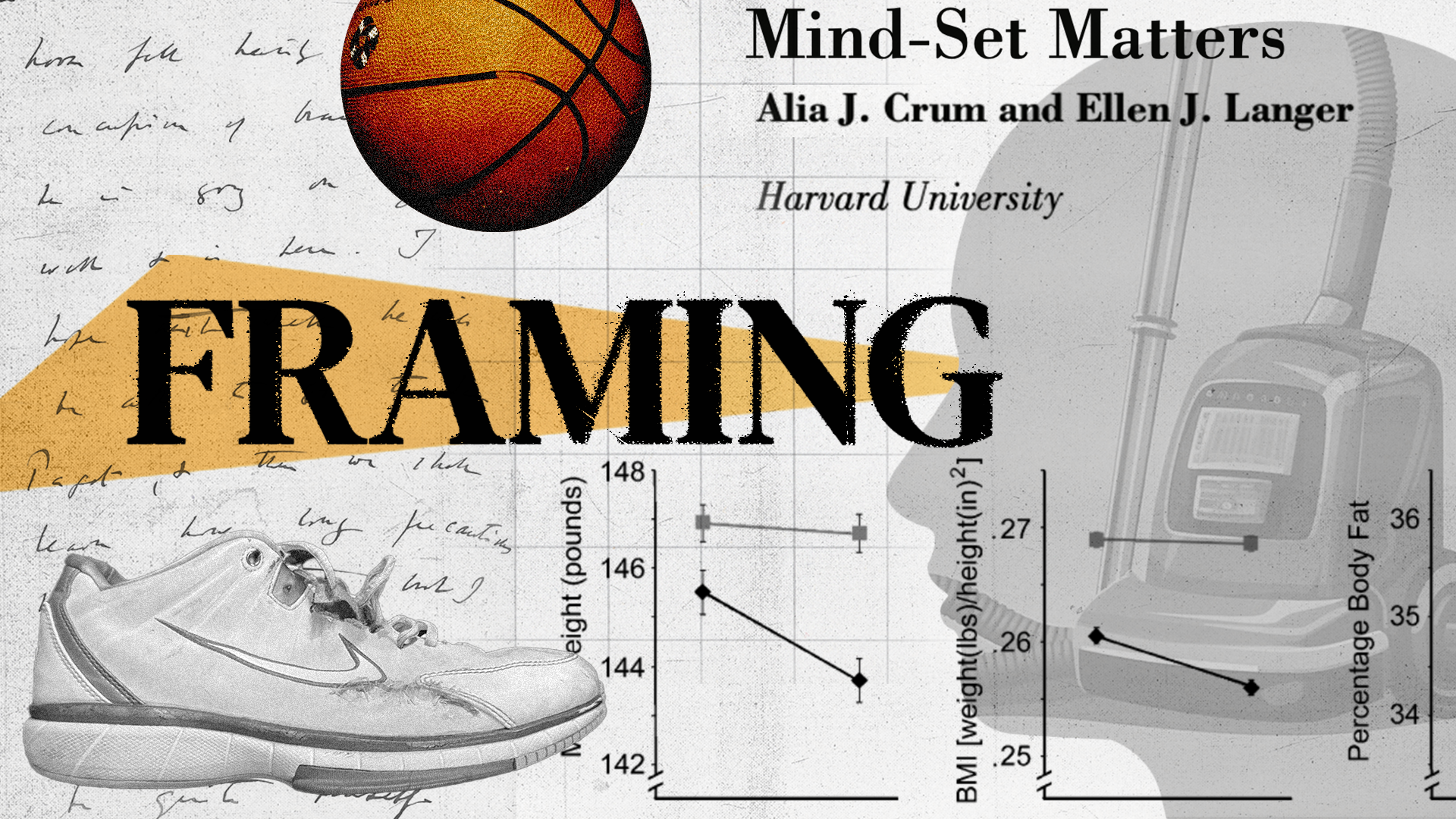

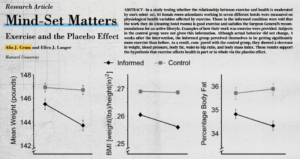

Ali Crum and her research team round up over 80 hotel workers. They divide them into two groups:

The intervention group, who is told that the work they do (cleaning hotel rooms) is good exercise and satisfies the Surgeon General’s recommendations for an active lifestyle. They are given specific examples of how their daily activities, such as vacuuming, changing linens, and cleaning bathrooms, burn calories and contribute to their overall physical health.

The control group receives no special training or instructions.

Four weeks later, the results are striking. The intervention group shows decreases in weight, blood pressure, body fat, waist-to-hip ratio, and body mass index compared to the control group. Neither group reports any changes in their exercise routines outside of work. Both groups are doing exactly the same job they’ve been doing, but are now benefiting from these actions in much different ways.

“Objective benefits depend on not just what we’re doing, but how we think about what we’re doing” – Ali Crum @TEDMED

Crum’s study looks at health, but the same rules apply when it comes to learning.

How we think about a situation can impact what we get from the situation. Let’s call that framing.

We’re all framing all the time.

I know that it happens in my workshops. If there’s an audience of 300 people, they are framing the session in a variety of different ways – and you can see it on their faces.

I can see when someone perceives the workshop as a threat: “Who is this young guy telling me what to do?”

I can see when someone is framing the presentation as meaningless, pointless – a waste of time: “I don’t need this, it doesn’t matter.”

And I can see when someone is framing the information as an opportunity: “Maybe this guy will share something that can help me.”

In most cases, framing doesn’t change the situation, but it can change how we benefit from it – and even whether or not we benefit at all.

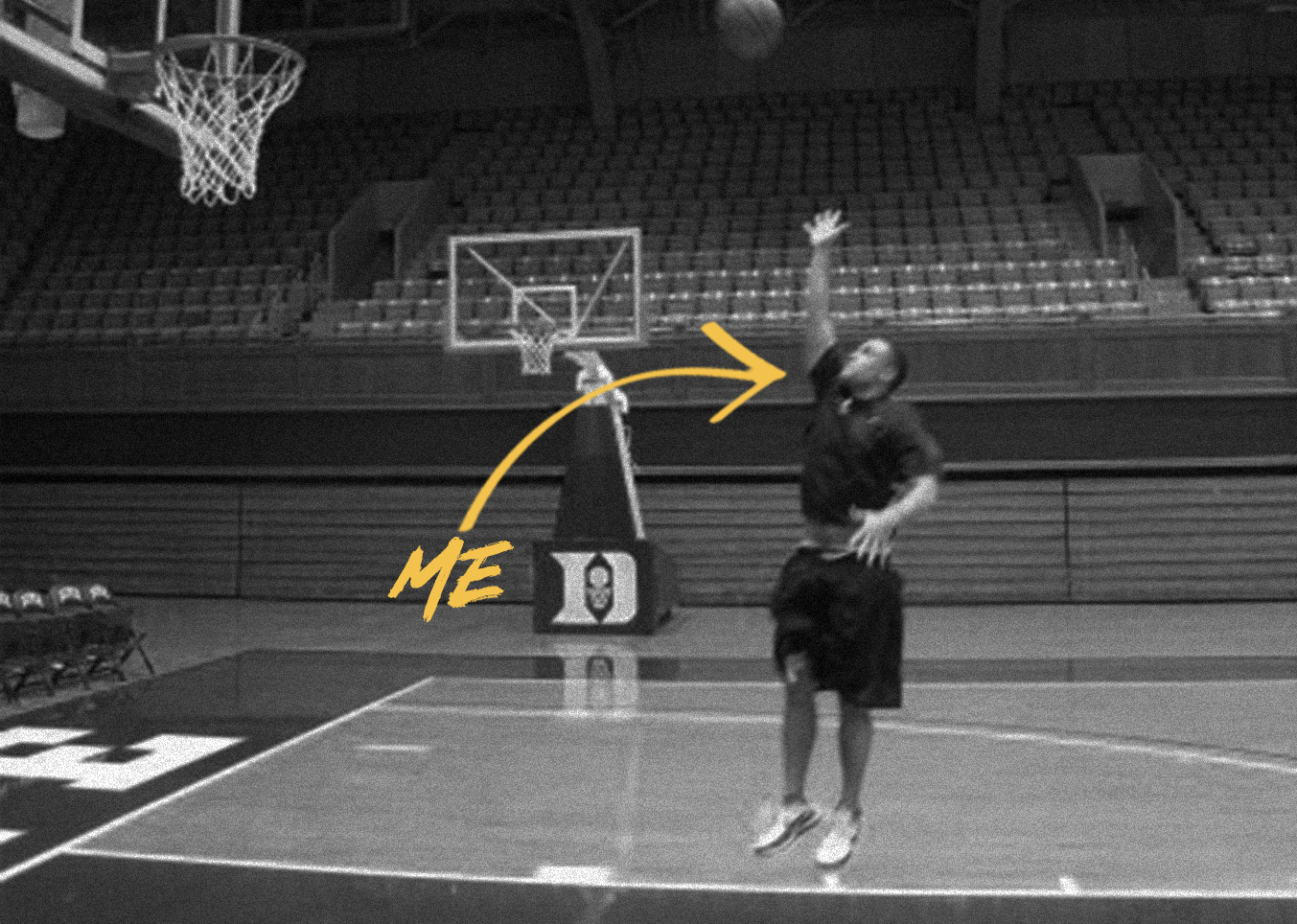

I’m an example of terrible framing.

Duke Basketball

From 5th-12th grade, pretty much the only thing I cared about in my life was becoming a good enough basketball player to play at Duke University – one of the best college basketball programs in the country.

This was a lofty goal for a 5’9” kid from Wyoming with extremely mediocre athletic abilities. But I wanted it, big time. And chased it hard. I practiced all of the time and I got pretty good.

Fast-forward to fall 2006, my freshman year at Duke. There are two spots remaining on the team that season. They hold open tryouts for the two spots and nearly 80 people show up.

I make the final four.

The four of us are essentially on the team for pre-season. We work out, scrimmage, and practice with the team. Coach K is there, Johnny Dawkins, Wojo, Chris Collins – my heroes that I grew up watching on TV. Every day that I walk to practice I’m crying. I’m so happy. I’m literally living my dream.

At the end of the preseason two of us will make the team. The other two will be cut.

I was the last person cut.

This story is not headed where you think it’s headed. This was not a sports movie where I practiced even more, even harder, then made it the next season. Nope. It was the opposite of that.

I did not handle this situation well at all. I was wrecked. I felt like a failure and that my identity was gone.

For two seasons I was a manager and occasional practice player with the team. I attended every practice, sat right behind the bench at every game. I was in on the team meetings and film sessions. I had a backstage pass to one of the best basketball programs in the country and front row seats to watch Coach K – one of the best leaders around – do his thing.

Whether you’re a basketball person or not, I think it’s clear that there were hundreds, thousands of learning opportunities floating around me for those two years.

I took advantage of none of them.

For most of those two seasons I was in a combo of threat/pointless framing:

They don’t think I’m good enough. This is embarrassing. I have to make Gatorade for the guy who beat me out. I didn’t make the team. I failed. What’s the point?

So I was mostly in auto-pilot, going through the motions. Was it enjoyable and fun? Yeah. Did I develop as many relationships as I could have? No. Did I learn as much as I could have? Absolutely not.

My mindset and attitude toward the situation robbed me of so much learning. I would give anything to do those two years over again.

William

On the other hand, William (name changed for privacy) is one of the best learners I know and an example of fantastic framing.

I met William in a prison in Kansas in 2015 while leading a workshop.

William and I connected before, during and after the workshop. We stayed in touch via email for a while. A few months later, he was released from prison.

Around this time I held a weekend hackathon. I convinced some of the most interesting people I knew to spend a few days in my apartment to develop new workshop material.

We had an Olympic coach, an Olympic athlete, a CEO of a startup incubator, and a couple of teachers. William joined as well.

It was the dream team of people all sitting around in my living room for three days.

I think some of the most powerful lessons and biggest takeaways for everyone in the room came from William. On the second day, William started to open up and share his story, his experience. He said he was in prison for almost 20 years, and for the first 15 he was really struggling. He was miserable because all he could think about was how terrible the environment was, how much he hated being there.

I can’t even begin to imagine how difficult that situation was for him.

But then, he goes: “With five years left in my sentence, I decided I was no longer in prison. I was in college. So I took advantage of that and I read, worked out, meditated. I just took advantage of having all of that time on my end to do something different.”

He starts just devouring books. He shares what he’s learning from these books with other guys on the inside. The group read Carol Dweck’s book Mindset and reached out to her. She doesn’t really do in-person workshops now, but she sent them to me. William was the reason I got to do the workshop where we met.Now that he’s out, he’s doing incredible things. He’s set up his own website and works with other people in tough situations. He’s even creating content to provide to other people on the inside to help them get out and stay out. One of the most phenomenal people I’ve ever met, one of the best learners I will ever know, doing amazing work.

All of this is a byproduct of him reframing his situation.

Did he change the environment he was in? No. Did reframing make every day fun and easy and light and enjoyable? No. Did he change what he got from the situation? Yes.

One thing that we have to be clear on with this topic: this is not blind or forced optimism where we ignore difficulties and problems, or minimize our feelings within the challenge. It’s the opposite of that.

This is being willing to accept the difficult situations, the things that are out of our hands, and all of the tough emotions that those situations can create, and at the same time, looking for the opportunities to grow and get better. This doesn’t necessarily make it easy, but it certainly can change what we take away from the situations we’re in.

Compare and contrast William’s story with my story at Duke.

I was in an ideal learning environment. The opportunities were glaringly obvious and right in front of my nose, but I didn’t take advantage of them – because of how I perceived the situation.

On the other hand, William was in a much tougher environment facing bigger challenges where the opportunities weren’t so glaring and obvious, but he was able to find them and grow from them because of his mindset, because of how he perceived the situation he was in.

There are big and small opportunities to grow in almost any situation. Our mindset and the way we think about the situation can either help or hurt our capacity to find them.

Framing in Action

Once we understand the power of framing, we can put this tool into practice.

Before, during, and after a situation ask: What can I learn from this? What can this teach me?

Asking and answering these questions will help us find and appreciate the opportunities within a challenge, setback, or really any situation we face.

Remember:

Framing usually doesn’t change the situation. Framing a situation as an opportunity does not mean we’re ignoring the problems, or the difficulty of the situation.

Framing is not blind optimism or toxic positivity. Framing is more nuanced than this is good or this is bad, I like this or I don’t like this. We don’t need to love the situation we’re in or enjoy the setback. We can feel sad, frustrated, even angry, and look for and appreciate the opportunities at the same time.

And yes, some things can happen in life that are total bulls*%$, where there may not be a lesson other than just figuring out how to move through it.

But you can try this out right now. Think of some of the big and small challenges you’re facing. Think about the questions above. More times than not, there’s something to be learned or something to gain if we take the time to check our framing.

Things that can help with framing:

Building a growth mindset and changing our mindset towards stress & discomfort can help with framing. When we believe we can change, grow, and learn – and when we’re more open to our tough emotions – we’re in a better position to find opportunities within a challenge.