A tiger living in the jungle is going to learn and develop more than a tiger living in a zoo. We made a video that presents the research that supports that statement and illustrates how we can apply the same logic to the way we learn.

The big idea: in order to become a better learner we need to spend more time out of our comfort zone – more time in the jungle where we experience challenges, solve new problems, and struggle. The theory is solid, but we need to be more specific and go deeper about how to actually put all of this into practice.

The video nailed why. Now let’s get into how…

HOW TO JUNGLE TIGER

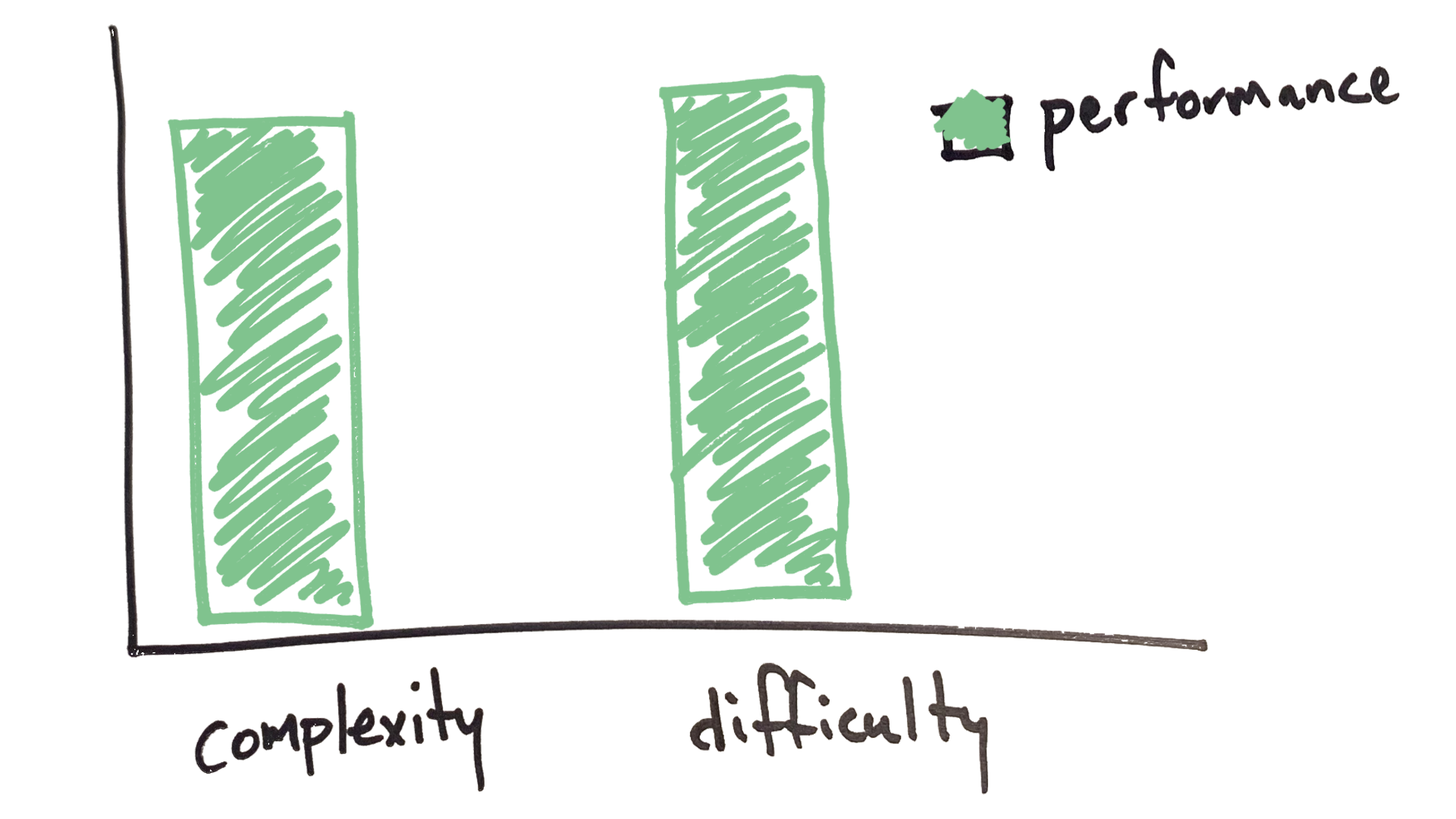

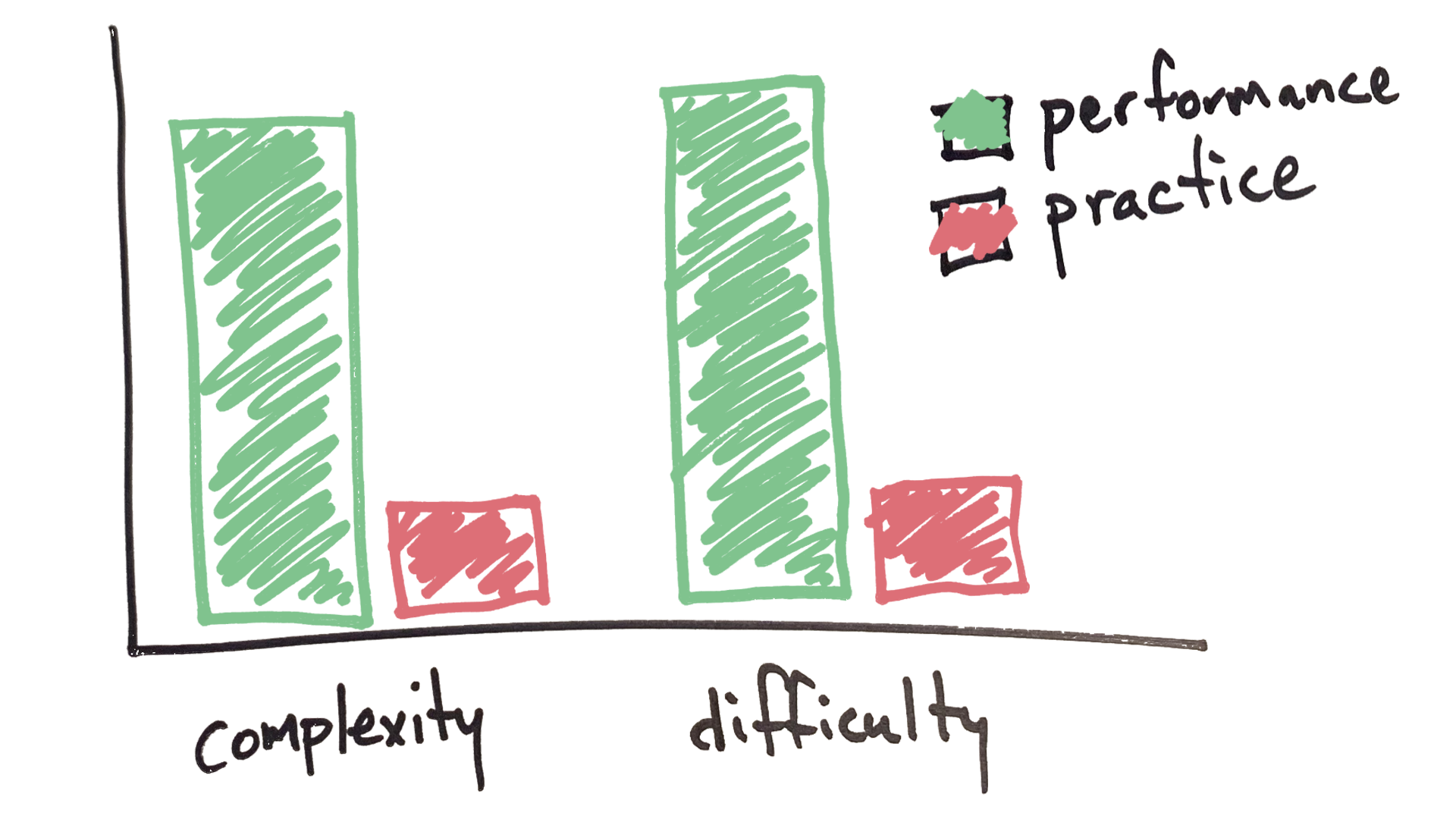

In school, sports, and the workplace our time is often split between performing and practicing:

The test, the game, and the presentation = performance

The things we do to prepare for the performance = practice

(obviously these aren’t the only two slices of the pie chart)

More times than not, the performance matters and we want it to go well. A great way to help that happen is to improve the way we practice.

Over the last 8 years I’ve had the honor of spending time with some brilliant researchers in the learning world: Anders Ericsson, Robert & Elizabeth Bjork, and Richard Schmidt. Their work points to a more effective way to practice, study, and prepare.

If we want to perform better, we need to practice better. Here are three tools to help us do that:

1. LEARNING SKILLS IN THE CONTEXT WE WILL USE THEM IN

Learning research shows that our practice is more effective when it resembles the performance. For the sake of argument, let’s look at these three scenarios:

A presentation

A test in school

A basketball game

In each of these scenarios there’s a considerable amount of:

Uncertainty – The outcome is unknown. I might make it, I might miss. They might buy, they might not. I might get this question right, I might not.

Unpredictability – I don’t know how the audience will respond or what questions they might have. I don’t know what questions are going to be on the test. I don’t know exactly where I’m going to shoot from, where the pass is coming from, or how open I’ll be, until it happens. No two shots, games, presentations, or tests are exactly the same.

Pressure – People are watching. I’m being judged. There’s a scoreboard. The outcome matters.

These variables and hundreds more make the performance and the skills we need to deploy extremely complex. To succeed when it matters we have to be able to adapt, make decisions on the fly, and execute our skills in the complexity of a situation.

The performance is complex. The performance is difficult.

A good presenter is someone who can walk into a room and execute while experiencing the uncertainty, unpredictability, and pressure of the given situation.

A good test taker can sit down, with no notes, recall the information they’ve studied, and put it on paper.

A good shooter can catch a pass coming from a different angle, at a random location, and determine how far they are from the rim. They can plan exactly how hard to shoot the shot even with a defender running at them – on the first attempt. Not the 5th or 25th.

In order for us to perform at our best we need experience executing these skills in the context they’ll be used. Unfortunately, the way we typically study, practice, and prepare minimizes or even eliminates these variables.

We rehearse our presentation dozens of times in front of the mirror with no audience.

We read and re-read the chapter.

We shoot from the same spot with no defense several times before moving to a new spot.

When we eliminate the context and variables of the game, the practice gets easier, and we make fewer errors. This creates a big gap between our practice and performance environments – which is not optimal for learning.

Let’s take it back to the two tigers.

The uncertainty, unpredictability, and pressure of the performance makes it a lot like the wild. A tiger that spends its whole life in the zoo and then is thrown in the wild doesn’t stand a chance. The same rules apply to our practice. We can’t practice in the zoo and expect to thrive in the wild.

The jungle tiger learns to thrive in the wild by spending time in the wild. If we want to thrive in the game, we need to spend more time practicing like the game.

A few things to keep in mind:

Our practice is never going to be exactly like the performance, and that’s okay. A good approach is to make a list of some of the variables you’ll face during the performance and find ways to incorporate them into your practice.

We can progress up to this. There’s nothing wrong with getting the hang of things in a more controlled environment. The goal is to spend more time dealing with the game variables and we can slide in this direction more often than we do.

Example: If we’re teaching a five year-old to hit a baseball, using a tee some of the time is just fine. After that should we move back sixty feet and six inches and throw them heaters with a regulation sized ball so they can be a jungle tiger? lol, no.

However, we could find a dodgeball sized ball, stand ten feet away and pitch to them. They’ll be able to connect with the soft, large ball, and they’ll be practicing the skill of hitting, in the context they’ll use it in: making contact with a ball that’s flying at them. Their eyes and brain will have the opportunity to read the speed and location of the ball as it moves towards them. They’ll get better at swinging at the right time and location to make contact, skills we can’t really build if we spend all of our time on the tee.

As we move through the rest of the article you’ll see how these additional tools can help add more context to our practice. They will make it more like the game which will help prepare us for performances.

2. DESIRABLE DIFFICULTIES

When exercising we build in difficulties. We add weight to induce struggle because we know that’s what we need to get bigger, faster, and stronger. We’re constantly stretching out of our comfort zones to produce results. The same rules apply to learning. In order to really make a change in our brain and build new skills we need some struggle.

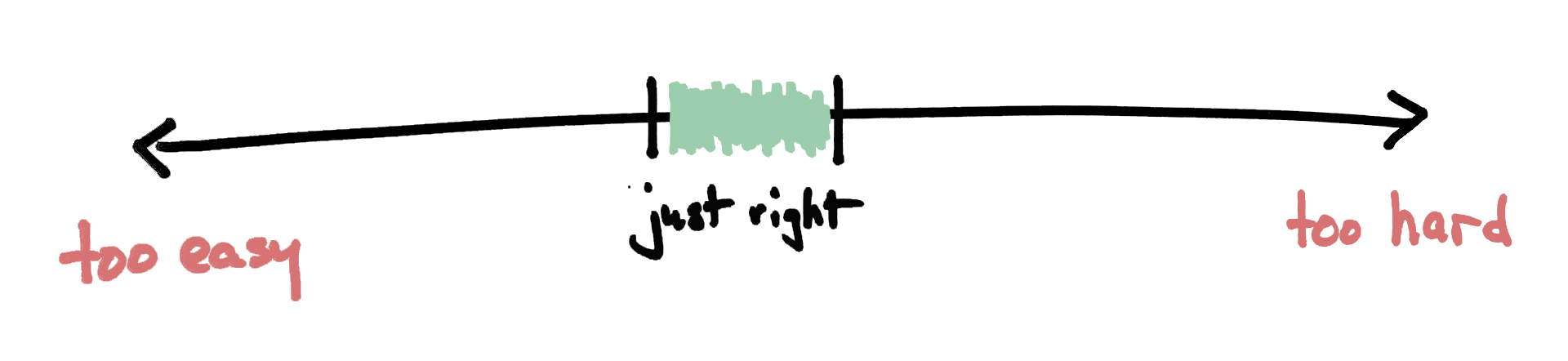

Similar to the weight room, there’s a right and wrong approach to this. It’s not fair to oversimplify this and say “harder is better.” In order to boost learning it needs to be the right amount of hard and right type of hard.

The Right Amount of Hard

If I’m doing squats there’s an ideal window of weight that’s going to be the most effective for me. If there’s no weight there will be little change. But the same is true if there’s too much weight and it’s too hard.

In order to see the results I want, I need to pick a weight that falls in this window.

Learning researchers Robert and Elizabeth Bjork call this optimal type of hard “desirable difficulties.” Desirable, because it leads to the best learning – not necessarily because we enjoy it. This window is different for everyone. It’s dependent on the skill we’re trying to build and our current skill set. The amount that I should be squatting is probably different than the amount you should be squatting. Finding this window can be tough but with some experimentation it’s something we can all do. One helpful trick we can use, especially in sports, is benchmark stats.

In basketball a good three-point shooter is going to hit around 40% of their shots. If I make a drill where that player is hitting 80-90% of their shots, it’s too easy, and not optimal for learning. Again, some of this is fine, but we shouldn’t spend all of our time there. The same is true if I build a drill where they’re only hitting 10% of their shots. This is probably too hard and also not optimal for learning. If we build a drill where the players are hitting 30-50% of their shots we’re probably in a good spot. However, we aren’t saying that we must spend ALL our time in this window. It’s simply something to be aware of and something we can utilize more.

This is easy to use in sports where we have these benchmark numbers but I’d imagine with some creativity we could use this approach elsewhere. When there’s no stats available we can use our feelings. If our practice feels too easy and too comfortable we can ratchet it up a bit. If it feels too hard and too overwhelming we can dial it back a bit.

I do some consulting work for a major league baseball team that’s working on implementing desirable difficulties into the way they train their hitters. During one of our workshops we asked them to come up with rough percentages of the swings a player gets throughout the week. We ended up with something like:

60% off a tee

25% in the batting cage

10% batting practice

5% in a game/game-like setting

When we looked at the numbers it was obvious that the players are getting lots of zoo tiger reps and were spending too much time in the easy zone. Obviously there’s value in all of these types of swings and practices, but we all agreed that we need to find ways to get the players more game-like swings, and doing that will make a big difference. By simply boosting the game-like swings to 15% we’re literally tripling those valuable reps.

The Right Type of Hard

There’s a right amount of hard and there’s also the right type of hard.

Some people get sold on this idea that we need to build difficulty into practice but they incorporate the wrong type of hard. Let’s call this fake hard.

The best examples of fake hard come from the sports world. Ridiculous drills and stunts fill up our twitter and instagram feeds. A basketball player is standing on a balance ball catching tennis balls with one hand tied behind their back. Is it hard to do that? Yup. Is getting better at standing on a balance ball, catching a tennis ball, with my hand behind my back going to help me dribble a basketball through traffic? The research says: not really.

Just like all the trust falls in the world are probably not going to help a team build real vulnerability and trust.

Two good questions to help avoid fake hard during our preparation:

Am I getting better at the drill or better at the skills the drill is trying to teach?

What is the actual skill I’m building right now?

If we can’t recognize the skill, its complexities, and how we’ll use them in the performance – we’re probably on the path of fake hard.

The best way to build difficulty into practice is to use the variables we’ll face during the performance: uncertainty, unpredictability, pressure, etc…

When we build this desirable difficulty and struggle into our practice and preparation, we’re going to boost the learning, which will help us perform better in the game.

Another upside is that the more we engage in difficult situations, the more used to that level of discomfort we become and can deal with it more effectively during the performance – because it’s something we have practiced.

3. STAYING OUT OF AUTOPILOT

When practice becomes too easy, too predictable, or too stable our brain will slip into autopilot. When that happens our perceived performance goes up, but learning and retention will suffer.

In short: autopilot is the enemy of learning.

In order to get the most out of our practice and perform at our best we have to keep our brain on its toes, out of autopilot, and engaged in learning.

Spacing

May 1st-25th, 2018 was an intense stretch of life for me. I had agreed to do two separate TEDx talks that month – one on the 12th and one on the 25th. It sounded awesome months before, but turned out to be fairly stressful as it approached. These two performances mattered very much to me and a lot of practice had to happen in a short period of time.

After I created an outline for the talk I would spend hours running through it back-to-back-to-back. If I messed up on a section I would start over and run through it a few more times. After the third attempt I felt like I had it down…

And yet…

The next day I would struggle on the same section. Why?

Your boy was falling into a common practice trap.

When we do the same thing a bunch of times in a row with no spacing our brain can dip into autopilot. We feel like we’re fixing the problem but in actuality the autopilot gives us a false sense of progress.

Autopilot feels good, autopilot looks good, but it’s not optimal for real learning to take place.

While practicing for my TEDx talk, if I made a mistake, I would immediately give it another go. Of course I’m going to do better on that second round because the mistake is fresh in my mind and easy to correct. However, it’s so fresh and so easy, my brain is going to slip into autopilot, and this progress will likely not stick.

That May, once I introduced spacing my practice made a huge leap forward. I made myself wait a minimum of sixty minutes between each attempt. This was more difficult but it activated my brain in a different way. Correcting the errors felt slower but once I got there the progress would stick.

“In order for real learning to happen we need to let a little forgetting happen.” – Elizabeth Bjork

We fall into this trap all the time when we’re reading – especially if it’s in preparation for a test.

We read a chapter knowing the material is going to be on the test and we really want it to sink in. So what do we do? Immediately re-read the chapter. The second run-through feels good. The material is fresh and it feels like we know it:

“Yup, yup, yup, I remember that. Cool cool. I got this.”

A-U-T-O-P-I-L-O-T

Research shows that there are exercises that will lead to better retention than re-reading material such as: quizzing ourselves after the chapter, calling someone to explain the key points, or implementing spacing between attempts. These exercises may be difficult but they produce better results.

We screw this up all of the time in the basketball world.

A common way to practice free-throws is to bunch all of the reps together at the end of practice: “Ok everyone go shoot 50 free-throws before you leave.”

Uh oh. I’m sure you can see some of the problems with this approach by now.

After the first couple of attempts I get in a groove. It becomes easy and my brain enters autopilot. I will make a bunch of these shots. Again, this is false progress. These reps are not game-like and there’s no spacing.

Over the past few years a couple NBA teams have discovered that it’s more effective to distribute the 50 free-throws throughout practice. Instead of all at once, they will do two at a time.

The players are getting the same amount of reps but because of spacing these reps are more effective.

The fun part is getting creative and making these reps even better. There’s no blueprint but we can find ways to introduce game variables: pressure, fatigue, etc. Once we understand some of these principles we can find ways to improve our old practice strategies.

Small adjustments can make our practices way better.

Spacing helps improve practice because it keeps our brains out of autopilot which leads to more retention. It’s also good because it makes the practice more game-like. During the TEDx talk I didn’t get to do three practice runs beforehand and I definitely didn’t get 48 warm up free-throws before the two that count.

Variation

Another way to keep our brains out of autopilot is to introduce some variation into our practice.

After a few rounds of running through our flashcards we start to memorize the order and know what’s coming next. That’s autopilot, friends. Simply shuffling the deck after each run would make the practice more effective. Sure, it will be a little more difficult not knowing what’s coming next but this small adjustment can keep us out of autopilot.

I’m a math teacher. I just taught my students a new formula. I want my students to practice using this formula so they remember it. I assign them a problem set with ten questions all involving this formula.

The students are likely going to fall into autopilot here. There’s no decisions to make beforehand. They already know the correct formula to use. It would be better if a few of the questions on the problem set involved formulas that we’ve previously covered. These problems will shake things up, and build more engagement into each question. This will help keep the students out of autopilot, and boost retention.

I’m a basketball coach. I want to teach my team a new play, we’ll call it play #5 (creative, I know). After teaching my players how it works (maybe I draw it on the board and let them run through it a few times) it’s time to let them try it live in a scrimmage.

“Run play #5!” I yell.

Ben stands in the wrong place and Hank sets the down screen too early.

I stop the play and make the corrections.

“Ben, you have to start here. Hank, you have to wait to set the down screen. Okay. Run it again.”

The second attempt is flawless. Ben is in the right place and the timing of the screens is perfect. But of course it is, we just did it. Ben and Hank are on autopilot.

It would be more effective if I stop them after the first attempt. Make the necessary adjustments and then say: “Ok run play #3!”

They run play #3. They go play defense. A few possessions later it’s time to give play #5 another go. Ben and Hank really have to focus here and if they get it now it’s really going to stick.

As you can see, variation works a lot like spacing. It keeps us out of autopilot and it allows us to work on skills in parallel. If we’re only using spacing we’re not really doing anything between reps. If we’re introducing variation, we’re practicing additional skills, while avoiding autopilot.

Variation comes in all shapes and sizes. On the driving range I can switch clubs between each swing, but I can also change the shot or target while using the same club – both are better options than mindless, autopilot inducing, repetitive reps.

There’s no need to overcomplicate this. When practice is too easy, too predictable or too repetitive, we’ll fall into autopilot. When on autopilot we get a false sense of progress. This is a trap and won’t lead to real retention. Spacing and variation are tools to make practice more difficult (in the right way), keep our brains out of autopilot, and increase the learning that happens during preparation.

As you can see there is no blueprint to all of this but these three principles of learning can make our practice a lot better. We don’t need to make sweeping changes here. Small adjustments can lead to big upgrades in the quality of our practice and preparation.

Of course, we don’t need to spend all of our time in the jungle. But it’s something we should work to do more often during practice. How much more? More than you think.

As we build practices for ourselves and others keep these three questions in mind:

1. Is it game-like?

2. Is it the right type and amount of hard?

3. Are we staying out of autopilot?

Click the poster to download the free high-quality print file. If you would like it professionally printed and shipped to your door, visit our shop!