Building resilience can help us become better learners. Let’s outline four tools that can help make that happen

by Trevor Ragan and Alex Belser

PART 1

Challenges, obstacles, adversity, and struggle are inevitable in life – especially when we choose to spend more time out of our comfort zone.

They’re going to happen – we can’t change, or control, that.

The bad news is: We can’t choose what happens to us

The good news is: We can choose how we respond to what happens

When we’re resilient in the face of a challenge we can influence two important things: how we move through it and what we get from it. And those matter, big time.

It won’t be easy but this is a skill we can all get better at.

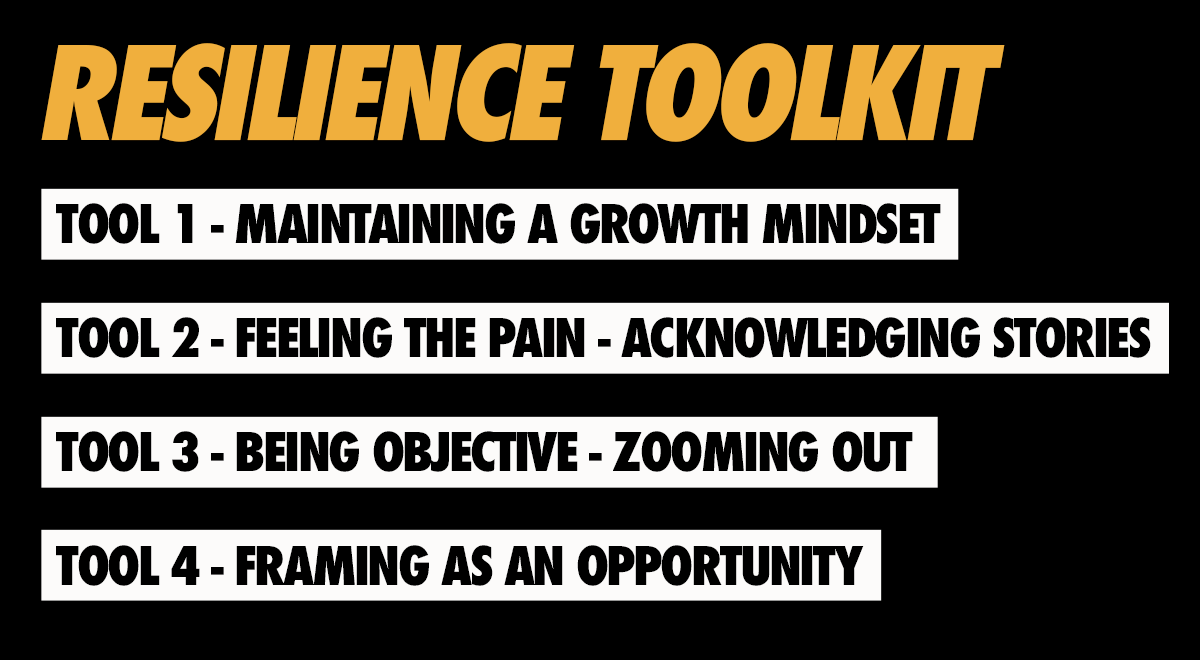

Obviously challenges come in all shapes and sizes so there is not simply one blueprint to becoming more resilient. Our goal here is to outline four powerful tools that we can pick and choose from, depending on the situation we’re in. Think of it as a Resilience Toolkit.

Moving through, and learning from, a challenge is not a race. This could take days, weeks, months, or even years. Understanding these tools won’t necessarily speed up the process, but they will definitely change how we experience it, and what we get from it.

This will be the longest thing we’ve ever posted on this site – but I think it might be the most important and useful. Our goal here is to:

PART 1: Upgrade our understanding of the resilience process – especially what can help and hurt it

PART 2: Unpack four important tools that can help us become more resilient

PART 3: Provide a framework and real world examples of how these tools work in different situations

ENEMIES OF RESILIENCE – THE THREE Ps

Psychologist Martin Seligman’s research uncovered the Three Ps as major hindrances to recovery from adversity:

Personalization – the belief that we are at fault

Pervasiveness – the belief that an event will affect all areas of our life

Permanence – the belief that the aftershock of the event will last forever

“It’s my fault this is awful. My whole life is awful. And it’s always going to be awful.” (From Option B by Sheryl Sandberg)

When we’re here it’s virtually impossible to move through the challenge, let alone learn from it.

Seligman’s studies have shown that we move through adversity better once we realize and acknowledge that:

It’s not entirely our fault – it’s not personal

It doesn’t mean everything is awful – it’s not pervasive

It won’t be awful forever – it’s not permanent

So the goal is really to avoid slipping into the Three Ps. When we recognize that negative events are not personal, pervasive, or permanent we are better equipped to deal with the setback.

Problem: When we face a challenge we often fall into the Three Ps

Solution: To build a Resilience Toolkit to help us avoid falling into the Three Ps and grow more from the challenges we face

PART 2

RESILIENCE TOOL #1 – MAINTAINING A GROWTH MINDSET

We’ve talked about growth mindset A LOT on this site. But we’ve only really used it in the skill development arena:

I believe I can grow – I’m more likely to do the work – I’m more likely to grow

The belief that we can grow is the fuel that drives the learning process. Well, this same belief plays a vital role in resilience too.

When things get hard, when we’re faced with a challenge, when we fall – the belief that we are not stuck, that we can change is absolutely ESSENTIAL to resilience.

This is not fake optimism:

“This is easy” “There is no problem here”

It’s the belief we can change, grow, and adapt – that we are not stuck where we’re currently at.

Maintaining this belief does not instantly diminish our problems. It still takes time and will involve some bumps and stumbles. But with some effort, time, and experimentation, we can absolutely move forward.

Larry Wilkins explains it best:

“With a growth mindset, once I experience failure or adversity. It’s like, ok – I’m really in a bad place right now. It’s a reality that this is going on in my life right now, this is a tragedy, this happened – but I don’t have to be stuck there.

Not saying that you run from reality, or you don’t accept what’s going on in the environment. The goal is to not let that take you over, to not let that blind you, or cut you off from have a vision of seeing further than that.

With a growth mindset it’s saying, ok this happened. This was a set back financially, this was a setback relationship wise, it’s a setback on whatever level – but the growth mindset allows me to start to move out of that and move forward.”

Problem: When we face a challenge, our fixed mindset stories can emerge: “I’m stuck, this won’t get better, I can’t change this, this is all my fault.”

Solution: Acknowledge the magnitude of the challenge but remember that we’re capable of growing and moving through it.

Obviously there’s more to the resilience equation than simply believing. But it’s a necessary fuel that helps us get started in the right direction.

RESILIENCE TOOL #2 – FEELING PAIN & ACKNOWLEDGING STORIES

A couple years ago, I went through a really difficult breakup. It involved phone hacking, lying, cheating, leaving in the middle of the night on a 10 hr drive to Omaha, and locking myself in a hotel room for three days – the usual.

It ends up that the drive to Omaha was one of the most important events of my life. It was a rollercoaster that played out in three acts:

Act 1 – Sadness & shame & stories

I was hurting. I was embarrassed. I was ashamed. I felt small and ridiculously sad. Tears rolled down my cheeks as I hopped on I76 W

Real thoughts I had and stories I told:

Nobody has ever felt this bad.

I am so weak for feeling like this.

She was probably cheating on me our whole relationship.

She was never really into me.

If I was smarter/funnier this wouldn’t have happened.

If I was in better shape or better looking this wouldn’t have happened.

I must not be good enough for her.

Act 2 – Anger & blaming & more stories

Enough moping – it was time to ‘toughen up’ and stop pouting…

I hit up a gas station, loaded up with some caffeine, got back on the road, and blasted a certain Big Sean song… on repeat.

All I could think about was how horrible she was for hurting me and how stupid I was for not figuring it out sooner – she was the WORST.

I called my best friend, he took my side, told me how awesome I was, and helped me lather on the blame even thicker.

This thrashing, suffering, blaming approach made me feel better.

For awhile.

But I was soon to find out that there was a much better way of dealing with a setback like this. People have researched stuff like this for decades, and that my actions were predictable and expected. As usual, science reveals a better way.

Act 3 – Curiosity & Queen B

I don’t know how, but a little seed sprouted up out of the blaring music and caffeine – a memory of a book. A book that had sat, unopened, on my shelf for the past year.

Rising Strong by Brené Brown

I pulled into a McDonald’s parking lot, parked close to the building, signed onto their wifi, and searched for Rising Strong on iBooks…

The description read:

“The physics of vulnerability is simple: If we are brave enough often enough, we will fall.The author of the number-one New York Times best sellers Daring Greatly and The Gifts of Imperfection tells us what it takes to get back up and how owning our stories of disappointment, failure, and heartbreak gives us the power to write a daring new ending. Struggle, Brené Brown writes, can be our greatest call to courage and rising strong our clearest path to deeper meaning, wisdom, and hope.”

Shut up and take my $17.95 already.

(To keep it real – I def went in and grabbed a few McMuffins and a large Dr. Pepper for the road).

Words can’t describe how Rising Strong spoke to me. It was the perfect book at the perfect time. Between the remainder of the drive and the three days I spent in a hotel, I actually listened to it twice.

After this four day bender, I had to get it together because I was scheduled to spend two days in Fort Dodge, Iowa speaking to groups of middle school students. It was my second trip to the school so I decided to roll the dice and build a new session, inspired by what I had been through, and what I learned from Brené Brown.

The first few talks were sloppy but by the third or fourth attempt I could see that this message was really hitting home with some of the students. Over the last couple of years, this exercise has become one of the most important and impactful sessions we deliver. I’ve had the honor of presenting it to some Fortune 500 companies, to hundreds of students and educators, and a few groups that were serving time in jail. Regardless of the setting or the group – the response and feedback has been amazing.

Here’s how we deliver it:

Round 1 – list as many examples of setbacks, failures, mistakes as you can in 90 seconds. They can be big or small – they don’t even have to be things you’ve experienced. No rules just write.

Then we share.

The most common responses we get are:

Rejection (not getting a job, making the team, or accepted into a school)

Poor performance (at work, in school, in sports)

Breaking up with a partner (one of the top responses for both adults and middle schoolers)

Failing a test

Losing a game

Missing a shot

Getting fired

Missing a deadline

Some of these are small, some big, some totally unfair. We could list about 500 things – but the point is, we’ve all faced some of these things (in one way or another) and will definitely face more.

Round 2 – how do we normally feel when we experience those setbacks and failures? List the specific emotions and some stories we tell

(someone in an auditing company I once worked with literally just wrote ‘bad’ on his paper – try to be a little more specific than that haha)

Again, the responses are consistent:

Sad

Angy

Not enough

Embarrassed

Disappointed

Ashamed

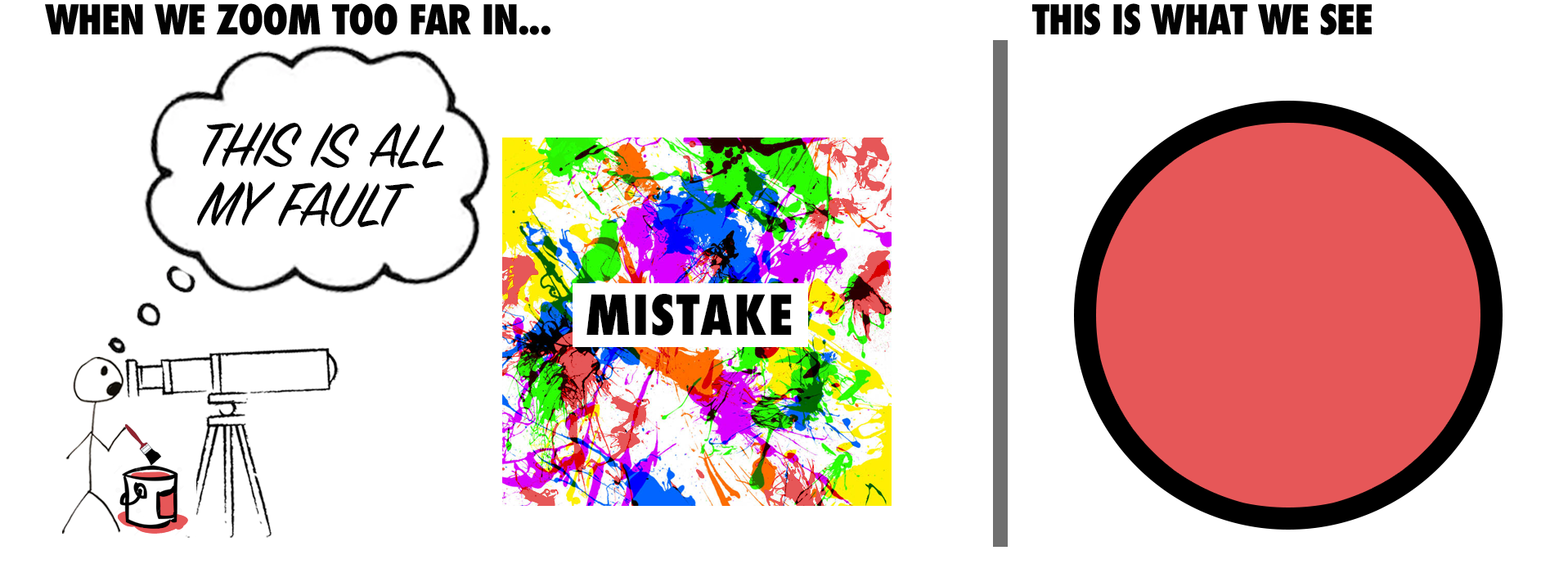

Defeated

Small

You’ve felt all of those things before, and so have I. And the truth is, when we fail we will usually feel a combination of them. And in that pain we usually tell a few stories about ourselves and the situation “this is all my fault” “I am not enough” “this will never get better” etc.. – just like I did in act 1.

Round 3 – how do we normally act when we feel those emotions? List the specific behaviors.

Most common responses:

Lash out

Blame

Isolate

Make an excuse

Cry

Yell

Quit

Eat/drink

This is where Brené Brown’s work really helped me the most. Her research shows that there are big, common, overarching categories a lot of these behaviors fall into:

When it comes to feeling these emotions and the pain and sting of failure we’re most likely to offload, numb, or hide.

We’ll call these three behaviors “pain relievers” because they’re the quickest/easiest way to get rid of the pain.

We’ve all done them. It’s human nature.

It’s kind of interesting (and scary) to dig into why…

Offloading is super common and there are two big ways we can do it: by blaming or by lashing out.

Blame: We do poorly on a test, feel angry, embarrassed, disappointed, etc… we don’t like feeling that pain and try to get rid of it ASAP, if we were to use the offloading through blame tactic, who could we blame it on?

Yup – the teacher.

If it’s the teacher’s fault do you see what happens? Pain = GONE. I don’t have to feel embarrassed or stupid anymore, because it was their fault. Whew.

Lashing out: This is when we have a bad day, and we go home and lash out on someone who had absolutely nothing to do with the bad day.…

Example: I struggled/failed, I feel pain, if I hurt – you should too, here – let me share some of this pain with you.

We’ve all seen this and done this, a lot.

Numbing is the 2nd pain reliever and it is pretty straightforward…

I fail, I feel pain, I don’t like feeling pain, let’s suppress and numb those emotions. We can do that with food, drinks, Netflix, you name it…

The 3rd pain reliever is Hiding – which means we stop doing the thing that caused the pain.

I apply for a job, get rejected, feel pain, and hiding would be?

Yup – I stop applying for new jobs. No more pain.

I’m missing some shots in a game, I feel angry/embarrassed, I stop shooting. No more pain.

Almost all of the responses people share will fall under one of these categories. They’re all human nature and sort of our default response to pain: pain = bad let’s find a way to get rid of it or find a way to not feel it again.

The problem is our default response usually isn’t the best. If we’re hiding, offloading, or numbing it’s going to be tough (if not impossible) to learn and grow.

Which brings us to the last brainstorm…

Round 4 – ideally how would we like to act and behave when we struggle and fail? List the specific actions.

We get a wide range of responses here but they almost always align with:

Accept it

Deconstruct it

Learn

Keep trying

Of course these are the responses. You know this, I know this. That’s not the point of this section…

Notice how we asked ‘how would we like to act when we fail and NOT how should we feel when we fail?

To be frank – the failures and setbacks from round 1 are not going anywhere, and neither are the emotions.. We’re all going to face so many more of them. Sure we can work on them, but the truth is when we fail there is going to be some pain. When we lose, get fired, or break up with someone – it’s going to sting, always.

Which is the hardest and most important part of this process.

Pre-Brené road trip to Omaha, I assumed (like I imagine most of us do) that the emotions = weakness. And when I was driving to Omaha, feeling all of the pain, I remember feeling a ton of shame about it “How are you so weak? You’re tougher than this. Be a man.”

After learning from Brené and another hero of mine: Glennon Doyle (author of Love Warrior), I realized that there is a difference between pain and suffering. And that it’s our actions, NOT our emotions that determine if we are weak or courageous.

Pain is the emotion we feel when we fail – we don’t have very much control over this.

Suffering is the negative or destructive actions we usually do when we’re in pain. Weakness is failing, feeling pain, and blaming those around us, lashing out on our teammates, making excuses, numbing, and hiding. Unlike our emotions, we have quite a bit of control over our actions.

It is impossible to suffer and grow at the same time. Because the tactics we use to remove or suppress the pain (pain relievers), rob us of the lessons and opportunities to grow.

Again, this is our default and it’s super easy to slip into.

Ways to suffer:

Tell stories that exaggerate the situation

Tell destructive stories about ourselves

Assume that pain is a sign weakness

Try to get rid of the pain

Looking back – I totally did this on the road trip!

I felt the pain in act 1. All of that pain lead to a number of “I’m not enough” stories about myself, as well as some exaggerations and assumptions about the situation itself. Rather than confronting these feelings and stories I took the easy way out and offloaded through blame in act 2: “She’s the WORST – It’s totally HER fault.” Pain = gone.

It felt good to be there – but I think it’s easy to see that I wouldn’t have learned anything from the experience if I had left it there.

Brené and Glennon show us a better way.

That it is possible – and usually necessary – to feel pain and grow at the same time. In order to find the opportunity, in order to really grow – we have to sit in the pain for a while. We have to own our stories and then get curious about them. THAT is courage.

The goal is not to immediately get rid of the pain and feel better. The goal is to take the next best action in order to learn and grow the best we can – and feeling pain and acknowledging our stories is the price of admission we pay to allow that to happen. We can’t get rid of them but we can stop them from fueling negative actions and behaviors – we do that by digging into them.

Courage is having a tough day but still being good to our friends and family. Courage is being rejected from a job, school, or team, feeling the pain, and still finding the opportunity to improve, and getting back out there again.

After finishing Rising Strong, I decided to stop blaming my ex for everything, to let the pain back in, own and get curious about my stories, and to try and learn. This was not fun or comfortable at all. But I realized that I actually played a huge role in this breakup and there were so many things I could learn from it and work on – which would help me grow and be better for my next relationship.

I would have missed out on all of that if I had just blamed it on her.

Brené calls this feeling our way through failure and Glennon calls it staying on the mat.

I think it’s about recognizing that we’re really going to battle against human nature and societal conditioning that tells us we shouldn’t feel pain.

Three things I want to be clear on:

First – This is not a race. I’m not saying that in going through a breakup we should stay up all night figuring out everything that went wrong and what to do better, download Bumble, and jump back into the game tomorrow… nah. There is no shot clock on this – we’re just presenting the process and principles. To be honest, this process usually takes longer than we want. That’s just how it is.

Second – The nugget or lesson comes in lots of different forms. Sometimes we realize that it was our fault (me during the breakup). And sometimes we realize that it wasn’t us – this happened during a workshop with a middle school group. One of the students shared how she was feeling and dealing with her parents’ recent divorce. How she put a lot of the blame on herself. By the end of the session she realized that it was not her fault, a powerful and important lesson

Third – Brené and Glennon are the experts here. They are our leaders – and if you’re interested in this you should definitely find a copy of Rising Strong and Love Warrior. They dig into this process, give amazing examples, and present some of the research. Also, and I can’t stress this enough, go to therapy if you can. It’s been one of the best and most important things I’ve done.

I know we went deep there. But I really think understanding this matters a ton.

Problem: When we look at emotions as a negative thing, we’ll try to get rid of them when we feel them, and that robs us of the opportunity to grow

Solution: Accept emotions, understand that it’s ok to feel them, stay on the mat, and feel our way through challenges and setbacks

Powerful questions to ask and answer in phase 1:

What emotions am I feeling?

What stories am I telling about what happened?

What stories am I telling about myself?

RESILIENCE TOOL #3 – BEING OBJECTIVE & ZOOMING

Now that we’re sitting in our pain and acknowledging our stories, it’s time to dig into them, to test them, to be objective about what really happened.

The stories we tell can exaggerate the problem, impede our ability to be resilient, and often send us back to the zoo. To avoid this, there are really three fronts we need to get real about:

Accepting the fact that it happened and focusing on what we can control and influence

The reality of what actually happened

The role we may or may not have played in the situation

Acceptance and focusing on what we can control and influence

This thing happened, we cannot change or control that. We can control our response and influence what we get from this challenge.

Let’s look at this through the lens of failing the first biology midterm.

We can toss things into three buckets:

What we can control

What we can’t control

What we can influence

Things we can’t control: our score for the first biology midterm. The questions on the second midterm. The way our teacher grades.

Things we can control: How long we study. How well we study. Who we study with. Whether or not we go to class. Whether or not we listen/take notes in class.

Things we can influence: our score on the second midterm.

Action is the engine that propels us through our adversity; however, our action needs to be focused on the right things. When we’re not sure where to start directing our action, it can be helpful to remember to separate things into our three buckets of: can control, can’t control, and influence.

Getting real about what actually happened

Here is where we put our stories to the test. A few questions can help:

“What do I actually know that happened?”

“What additional evidence do I need to better understand the situation or the people involved in this situation?”

A helpful exercise is to try to deconstruct the major cause of the event. Did this happen because:

An event or another’s actions are out of my hands?

An error in my process?

A lack of experience?

An event or someone else’s actions that are out of our hands

I was open, shot with great technique and rhythm but I missed the shot

Someone runs a red light and crashed into my car

A friend or family member gets sick

If it falls into category #1, it’s important to avoid taking it personally (more on that later). That doesn’t mean it shouldn’t hurt, it most likely will in someway or the other. But we should work to avoid making up stories about ourselves in response. And do our best to move through it the best we can, at whatever speed is appropriate.

An error in the process

I missed the shot because I was not open, or jumped off the wrong foot

I rear ended someone because I was texting and driving

I failed our math test because I didn’t study

Events that fall into category #2 are great learning opportunities. Especially when we can find the root cause of the problem. This is something that Toyota understood back in the day. Whenever there was an error in the production process of a car, they challenged themselves to ask why 5 times to get to the root cause of the problem – rather than just fixing what was on the surface.

Example:

A door falls off of one of their cars. Most companies would simply repair the door. That’s fine, but when we ask the 5 whys it gets better…

The door fell off. Why?

It wasn’t installed properly. Why?

The person who installed it was rushed. Why?

We are short on team members in that department.

Solution: Add another team member to that department.

This solution will have more of an impact than simply fixing the original door. Also, I know we only asked 4 whys in that example. There’s no magic about the number 5. The goal is to get to the root cause, with however many ‘whys’ it takes.

Think about the failed math test from before. A few ‘whys’ could get us to a fixable root cause – which will probably be more effective than a surface level reaction of:

“I failed the math test ¯\_(ツ)_/¯”

Note: The 5 whys are usually not helpful or necessary when dealing with an event that was out of our hands – we’ll just end up guessing and assuming.

A lack of experience

I missed the shot because I tried a reverse left-handed layup – and I never really practiced that shot before

I try to draw a bird, but it doesn’t look very good because it’s the first time I’ve tried to draw a bird.

This one is pretty straightforward. Look at it as a red flag that points out an area that just needs more work. It’s not fun to struggle or fall short but when we can chalk it up to a lack of reps, it’s definitely fixable.

Sometimes setbacks can fall into all three categories:

I apply for a job and get rejected. This could be due to an unfair hiring practices by the company (event out of my hands). Or maybe I stumbled on a few of their questions because I wasn’t as prepared as I should be (process error). Or it was my first job interview, and of course it’s not going to be my best performance. Or a mix of all three.

We’ll never get all of the details and fully understand how it all shook down – but the more concrete evidence we collect, the better.

This would have helped me a ton during the breakup because most of the stories I was telling about the situation and myself we’re based off assumptions I was making about the situation – not what actually happened.

Getting real about the role we may or may not have played in the situation

Sometimes we play more of a role than we’d like to admit (me going through the breakup). And other times we played a smaller role than we feel (the student feeling like her parents divorce was somehow her fault). I guess the idea here is to be as honest as we can about this – and usually our snap reaction isn’t the most accurate. The questions above can help with this.

Note: We do NOT have to do this alone. Sometimes a close friend or family member can be a great resource to unpack some of this with. Also, if it’s an option, going to see a therapist or counselor can be incredibly helpful. I’ve been going to therapy for the past few months and I can’t even begin to explain how powerful it’s been for me. 10/10 would recommend.

Now that we’ve tested our stories, gathered additional evidence, and tried to stay objective about what actually happened, it’s time to do some zooming.

What is zooming? Glad you asked…

Zooming out

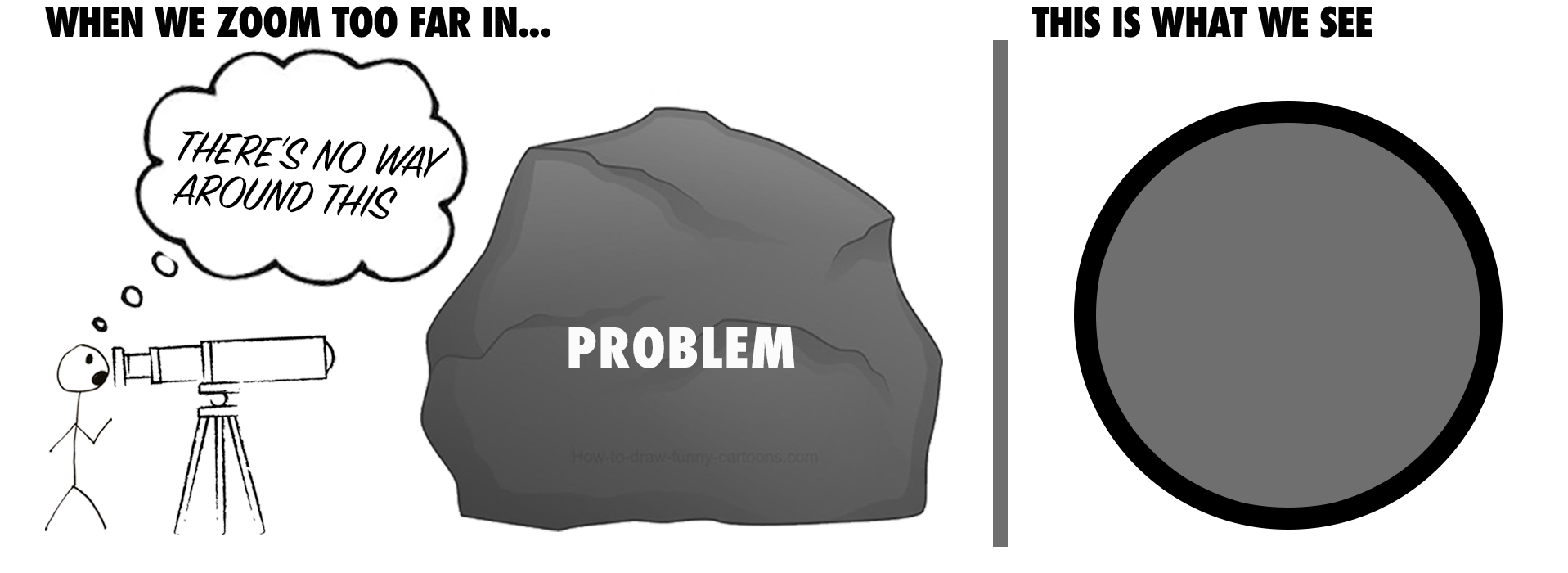

Usually our default approach when we face adversity is to zoom really far into it.

Here, it’s difficult to see the context of the situation, it’s easy to exaggerate the magnitude of the problem – where we’re unable to see a way through it, and it’s REALLY easy to take it personally. Basically, it’s going to drop us into the Three Ps that we’re trying to avoid.

Personalization: “This is all my fault – I am awful”

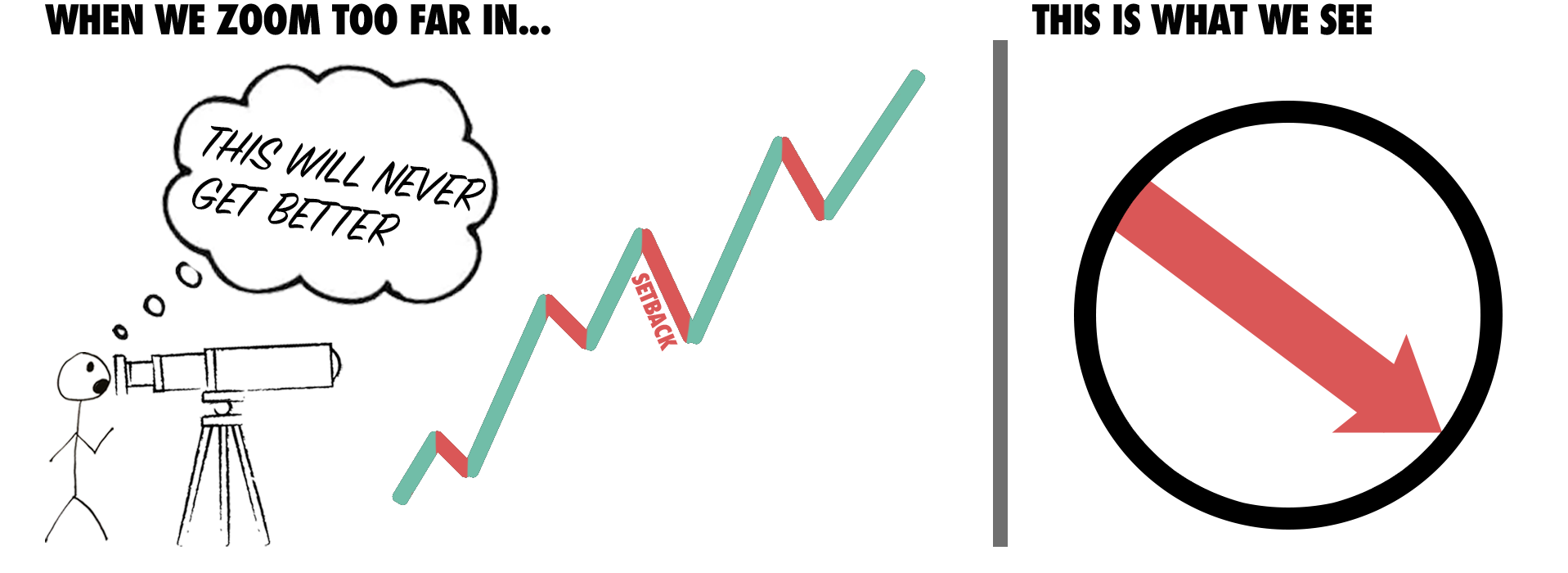

Permanence: “There’s no way around this – this will never get better”

Pervasiveness: “Everything is awful now”

So if zooming too far into the situation causes problems and likely slides us into the 3ps – what do you think the logical solution is?

Yup – zoom out.

But we have to be careful here. If we zoom too far out we lose sight of the situation all together…

“This is no big deal – I’m just a speck of dust in the universe”

“This problem doesn’t matter”

“What problem are you even talking about?”

This might seem like an effective coping mechanism, but this strategy removes meaning and purpose from our lives. When we zoom too far out, we can no longer see the meaning, the context, the role we did or didn’t play – and, most importantly, we totally lose site of the opportunity to grow within the situation.

We’re really looking for the middle ground here. When zoomed properly we’re able to take things seriously – not personally. We are objective about the role we did or didn’t play in the situation. We can focus on the things we can control and influence. We are able to put the setback into context – it’s a problem, it’s tough, we feel it but know that we can eventually move through it. Here we are better positioned to find the opportunity – which is the only way we’ll be able to grow from it.

Tip: We can use our emotions to help with zooming. If we feel nothing, it’s a signal that we’ve probably zoomed out too far.

Problem: Sometimes when we face adversity we zoom too far into it. Here our stories takeover and can exaggerate the problem, and we will most likely fall into the 3ps

Solution: Be objective about what happened. Zoom out, but not too much. Here we are positioned to learn as much as we can from the setback.

Now it’s time for the final, and maybe most important, step: framing

RESILIENCE TOOL #4 – FRAMING

We fell, we felt, we acknowledged and tested our stories, we zoomed, we believe we can grow – now it’s time to make sure that that happens.

Research shows that the way we frame a situation impacts our actions and how we approach it, which determines what we get from it. This should be empowering information because it shows that this is something we can control.

We mostly don’t control the problems, challenges, obstacles and changes that are thrown our way in life. But we can control how we experience them and what we get from them.

There are three big ways we can frame a situation:

As an opportunity

As a threat

As useless

We can look at the obstacle in front of us and say, “This is a threat. This is going to make me look bad. This is a bad thing for me.” This unleashes the downward spiral of negative self talk. We get caught up on the wrong things, our lizard brain is activated, we’re operating out of fear, we’re most likely zoomed really far in – and learning is going to be virtually impossible.

We can look at the obstacle in front of us and say, “This is pointless. This is stupid. It doesn’t even matter.” While this might help us move through the obstacle, we’re robbing ourselves of potential growth. When we frame something as pointless, we give up the ability to extract any meaning from it. This type of framing can come from our fixed mindset, or from being too far zoomed out.

OR

We can look at the obstacle in front of us and say, “This is difficult, but there’s an opportunity here. There is something to be learned from this experience – some way to create meaning and grow in the face of the challenge”

This is, without a doubt, happening with this article.

I guarantee that some people have closed it by now either because they framed it as a threat: “who is this guy telling me what to do,” or as useless: “I don’t need this, I already know this.”

And you, because you’re still here (which I appreciate btw), framed it as an opportunity: “maybe something in this can help me grow.”

Do you see that the way that this is framed has a bigger impact on what people get out of it than almost anything else.

The person who closed this tab after page 2 min was reading the same words you are. The difference was in the way that you two framed it.

You saw it as an opportunity and they did not.

You’re going to learn from it and they will not.

For 99% of my life, I absolutely HATED having to park far away from the entrance of a building. I was the guy who would circle like a vulture, waiting to pounce on the good spots, because having to walk a few extra steps was obviously not an option.

This year that’s completely changed because someone gave me a Fitbit for my birthday.

I’ve been wearing this thing for a while now, it counts my steps and encourages me to get a least 10k a day – there is a lot of research that shows that that is SO good for our brains. Anyway – now I LOVE parking far away from an entrance and actually do it on purpose…

Why?

Steps, yo!

It’s a chance for me to get a few more steps.

You see what’s happening? Wearing the Fitbit changed the way I framed the situation, which changed my actions and attitudes towards it.

Framing does NOT change the situation, but it can influence what we get from it. It’s everywhere and it matters.

Also, remember Larry from earlier? He’s one of the most resilient people I know and his story is the ultimate example of framing. We devoted an entire section to it at the end of this post – so hang tight.

A few quick things we need to be clear on:

Framing a situation as an opportunity does not mean we’re ignoring the problems, or the difficulty of the situation – this is not blind optimism. This is being realistic about the situation, zooming properly, and looking for the opportunity to learn and grow. Most of the time there will be something.

With that being said, some things can happen in life that are total bulls**t – where there may not be an obvious lesson other than just figuring out how to move through it.

Problem: the way we frame a situation has a huge impact on what we learn from it. Our fixed mindset will nudge us to frame things as pointless. When we’re operating out of fear, or too far zoomed in we’re likely to frame situations as threats.

Solution: Work to frame more challenges as opportunities

Whew… lots of pieces to our resilience toolkit? Feeling a little overwhelmed by it all?

Same.

Let’s put it all together into a more digestible framework and show how to use them.

Note: It’s important to remember that these are all tools at our disposal but we don’t always have to use them all. We may only need a hammer for some projects, others might require a hammer and a saw, a few might even require the whole toolkit. Just as important as having the tools is knowing when and how to use them – so let’s talk about that.

PART 3

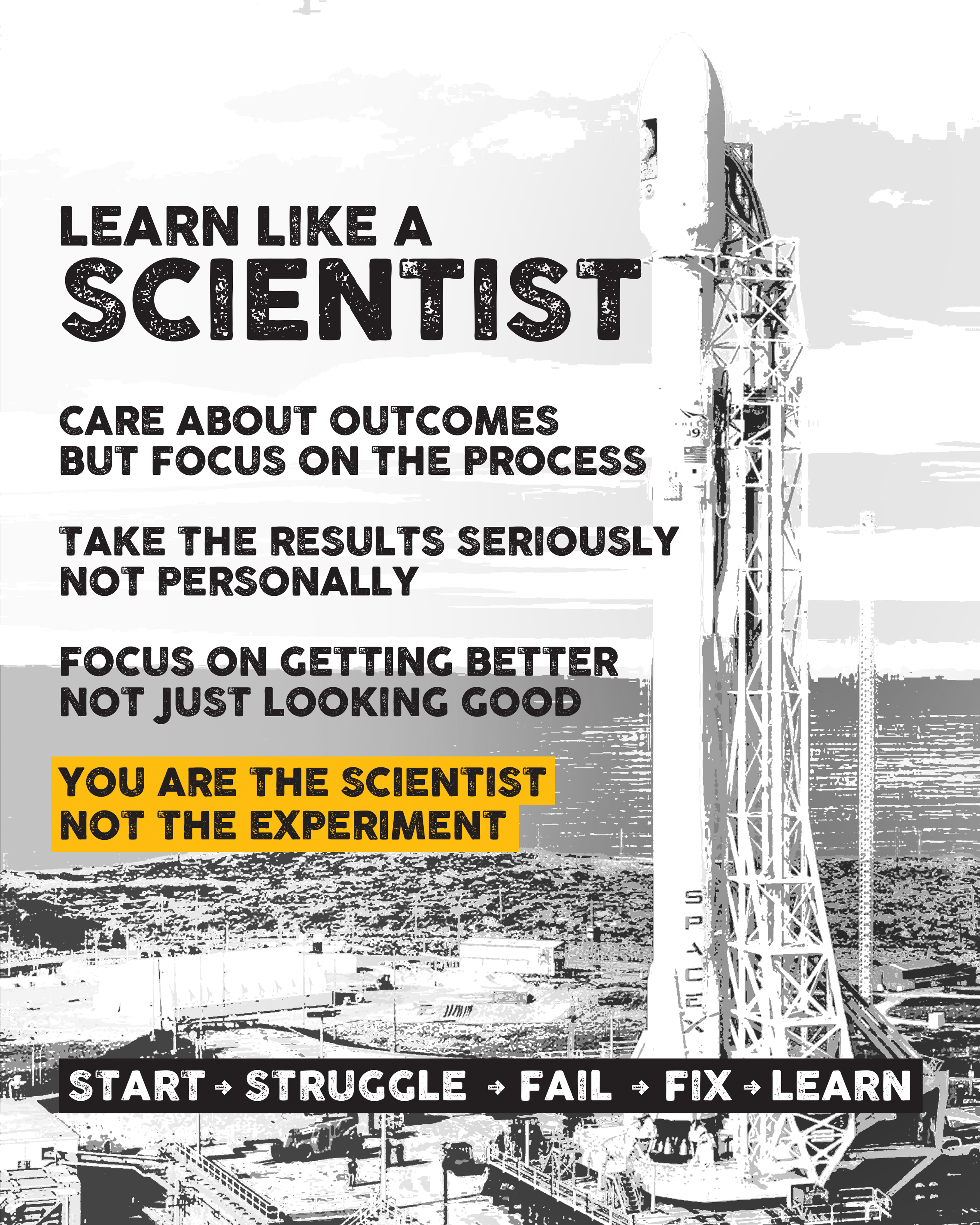

LEARNING LIKE A SCIENTIST

Scientists are some of the best, most resilient learners. And it’s all because of how they approach their job.

Scientists have HUGE goals and outcomes they care about and pursue…

Curing cancer, self-driving cars, colonizing mars, all are huge tasks

It’s not like they rock up to the lab and go “ok y’all let’s just learn as much as we can today…”

Nah.

There is absolutely an outcome, vision, goal, and explicit pursuit that they’re on.

But.

Scientists understand that simply obsessing over these outcomes and goals is not how to achieve them.

They know that outcomes are a reflection of the process.

So they obsess over continually improving their method and process. They do this by experimenting with it, by tweaking it, by breaking it, by seeking out knowledge and information from anywhere and everywhere.

They welcome feedback, mistakes, and failures because they know that these things provide valuable information that is helping to improve their process, helping them grow, and moving them closer to their goal.

What’s this process look like in the real world?

Elon Musk & SpaceX

Back in the day, Musk sold his share of PayPal for close to a billion dollars and then started a rocket company (as you do) with the goal of revolutionizing the space industry.

Space has always been slow and clunky.

Old school approach: We launch the rocket, it sends satellites and supplies up to space, we blow up the booster, then we spend millions of dollars and lots of time to build a new booster before we can launch again.

This is obviously a huge waste of time, money, and material. If we used this process for airplanes it would cost you like $3 mil to fly to New York.

Musk and SpaceX decided to change this.

New goal: A reusable rocket. One that we launch, that sends satellites and supplies to space, that we land back on earth like a pencil, and that is ready to go again – almost immediately.

Definitely a HUGE goal. One that many said was impossible – but they pursued it anyways.

What do you think they did a lot of in this pursuit?

Lots of pain, lots of frustration, lots of failing, for YEARS – yet they persisted…

This is what we really need to steal from scientists. Their process demands that they be incredibly resilient – and they show us how to use all of our resilience toolkit.

By understanding that the outcome (the rocket crashing) is a reflection of the process – they are one step removed from the equation.

Which allows them to take outcomes seriously, not personally.

When the rocket crashes…

of course there is pain

of course there is frustration

of course they care

But they know: the outcome is a reflection of the process, NOT of me as a person.

I am not a failure, the failure was in the process.

Seriously, not personally.

As Brene Brown says:” There’s a huge difference between “I made a mistake” and “I am a mistake.”

My favorite writer on the internet, Tim Urban adds his two cents: “The opposite of learning like a scientist is feeling like you are the experiment.”

When we’re the scientist, we’re testing our process, and always looking for ways to grow. When we feel like the experiment, our ego is on the line; “I’m a success, I’m a failure.”

If you think about it, scientists are putting the entire toolkit to work…

They maintain a growth mindset. The rocket crashed but we are not stuck here. We can eventually figure this out.

They feel the pain and frustration. They don’t let that stop them from learning what they can from the crash, building another rocket, and launching again.

They’re objective about what happened. They don’t invent stories about why the rocket crashed. They gather evidence, and they ask a lot of ‘whys’ to try and find out what actually happened.

They’re zoomed out. They know that in order to eventually land a rocket, they’re going to have to crash a few. Crashing is part of the process – and one failure doesn’t end them.

They’re masters at framing. When the rocket crashes, how do they frame the failure? Pointless? Nope. As a threat? Nope. As an opportunity? Yup. It’s feedback, it’s an opportunity to learn grow and get better.

Note: this doesn’t mean they enjoy the failure, they just know they can learn from it.

After going through this process for years, they’re finally figuring it out. At this point, they’ve landed dozens. They totally changed the space industry – cutting down the costs of a launch which will lead to unimaginable innovation.

They achieved something that will change the space industry forever, because they were down to struggle.

Whether we’re trying to land a rocket, or skateboard, or figure out how to walk – the process is the same.

Set a goal, try, crash, learn, try, crash, learn, try, crash, learn, try, crash, learn…(repeat for hours, months, or years) try, land.

The problem is most of us (me included) don’t learn like scientists.

Most of us zoom too far in and slip into the Three Ps.

Most of us take outcomes personally. Which means our outcomes are a reflection of us, as a person.

When our rocket crashes, we take it personally: “I’m stupid, I failed.”

When we’re zoomed in we lose sight of the bigger picture and context. We tell stories. We frame the situation as pointless, or most likely, a threat. And we’ll most likely find a way to stop.

I do this all the time, and so do you.

The good news is that we can change this.

Resilience is a skill we can all develop. We can all work to learn like scientists more often.

Think about a student that fails a math test…

Default response (taking it personally): “I suck at math. I am a failure. I am stupid.” Or it builds hopelessness: “This doesn’t matter anyways. What’s the point.”

If we teach the student to learn like a scientist they can work to find and fix the error that led to the outcome.

(i.e. – Dang! The rocket crashed, that’s not very much fun, but let’s figure out why it crashed.)

Did I fail because I didn’t study? Because I didn’t understand the assignment or a certain type of equation? Asking a few ‘whys’ would be helpful in this scenario.

Once we identify the error in the process we can go to work on fixing it: asking for help, improving our study habits, getting a tutor.

Same is true after a tough loss. Most of the time we zoom too far in on the loss. Where we’re likely to take it personally – which can lead to tension, excuses, and blame.

If we flip the script, own the crash, look into the process for things to tweak and fix, we will grow more, learn more (and win more) over time.

A missed shot, a poor decision, a bad grade, falling off the bike, and a spectacular crash of a $200m rocket ship all fit into the same category – they all provide useful information and feedback to our process. They are all tremendous opportunities to learn and grow – if we allow them to be.

This is definitely not the most comfortable or easiest approach.

Finding the opportunity in these challenges can be frustrating and hard – but it’s what the best learners do. And that is what it means to jungle tiger.

When we face a big problem, a big obstacle, or experience adversity – two questions can help us look for the opportunity and change our focus.

What would a scientist do?

What can I learn from this?

Let me tell you about one the most resilient people I know.

LARRY

I first met Larry in a State Correctional Facility during a workshop I was doing for a reentry program. The program is designed to prepare men on the inside to be reintroduced back into society.

After the workshop we kept in touch via email and on Feb 27, 2017, we had the opportunity to hang out in person, which would turn out to be one of the most incredible weekends of my life.

I picked 8 of the best learners I know and convinced them to come hang out in my apartment for a few days so we could go through all of this together. The thinking was if I could explain it all in person, get some live feedback, I’d be more prepared to put it all on paper.

We packed everyone into my living room and got to work.

There was an Olympic coach, an olympic athlete, a CEO from San Francisco, a college student from Wyoming, a woman from Boston who made a documentary about sexual assault, a teacher who had been in education for nearly 40 years, a college coach, and Larry.

Words can’t describe how incredible this was. At times it was extremely uncomfortable – having my ideas challenged by people I admire wasn’t that fun, it was awkward and confusing, I even got called out a few times. But so much growth and progress came out of those two days. If you like this book, it’s because of that weekend.

Perhaps the most profound lessons came from Larry.

On the second day he was sharing his story with us. A story that none of us will ever forget…

“I spent nearly 20 years at Lansing. And for the first 15 or so I was absolutely miserable. I suffered every single day. All I could think about his how much I hated there, how unfair that it was I was even there, and how horrible the environment was…”

(all completely understandable – actually, not understandable. I can’t even fathom what that would be like)

“With a few years left in my sentence I decided that I was no longer in prison, that I was in college. I had two things going for me; access to any book and lots of time on my hands. So I treated like I was in college and got to work on my education.”

Larry started devouring books, teaching what he learned to other people on the inside, played a huge roll in the reentry program that ended up bringing me in. He’s been out for about a year, works in conflict resolution (helping people both on the inside and out), has his own website, and he’s putting together a Reentry Mindset program to help others stay out once they get out.

All amazing things. All a byproduct of him changing and reframing his situation.

Did changing his focus and reframing his situation as an opportunity change his environment? No.

Did it make every day just super fun and enjoyable? Probably not.

But it did change what he got out of the experience? Yes! And that matters so much.

Most of us will never experience something like that. But all of us will face challenges and we can use Larry as a model of how to get the most out of them.

When we look to find the opportunity, we’re not blind to the problems, we don’t ignore the difficulties – we’re just being scientists. The rocket crashed, we can’t ignore or change that, but we can look for the opportunities and work to get the most from them.

Resilience is a skill, a muscle – and now it’s time to build it.

We have our toolkit, we have our models (scientists & Larry), now it’s about putting it all into action and getting the reps.

I hope something in here will help you do that.

FREE POSTER

(click to download print file)